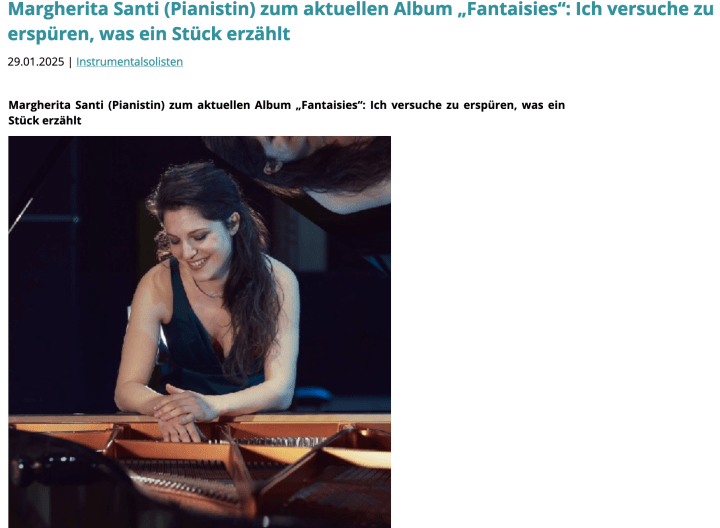

A new conversation between Margherita Santi, pianist, and Stefan Pieper, journalist, about the new album Fantasies, has been published on the Online Merker – Die internationale Kulturplattform.

With her new album Fantasies, Italian pianist Margherita Santi presents a remarkable exploration of musical fantasy as a form of artistic freedom. Her program spans from Mozart’s Fantasia in D minor, K. 397, through Beethoven’s “Sonata quasi una fantasia” in C-sharp minor, Op. 27 No. 2, to Chopin’s Fantasia in F minor, Op. 49, and Schumann’s “Faschingsschwank aus Wien,” Op. 26.

The 30-year-old musician, born in Verona and trained, among other places, at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, combines artistic excellence with a deep intellectual approach to music. As the founder of the Herbst Musicaux Festival in Verona, she creates new connections between music, other art forms, and her audience. In a conversation with Stefan Pieper, she revealed herself as an artist of high intellectual maturity, one who not only plays music but also pursues a broader societal mission through it.

The album was recorded in the neoclassical Villa Alba, perched above the lake, its bright walls glowing in the sunlight. The location was no coincidence—its special atmosphere, where legends like Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and other piano greats once performed, perfectly aligns with Santi’s artistic vision. In her discussion with Stefan Pieper, she emerged as a musician of profound intellectual depth, one who sees music not merely as performance but as a means of cultural and social engagement.

Let’s start with your new album. You chose a very special recording location…

Yes, Villa Alba in Gardone Riviera. It’s truly a magical place—a neoclassical villa with a vast garden. A few decades ago, some of the greatest pianists performed there, including Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli and many others. That special atmosphere is still palpable today. Concerts are still held there regularly, especially in the summer and early autumn.

What was the starting point for your current album Fantasies?

It developed over several years. Of course, I wanted to record these masterpieces, but I was searching for a deeper connection between them. I believe that composers did not simply write their music—they were truly inspired. As Plato said: Music does not arise from rules; it is not a science. Instead, composers discover it in a dimension beyond our everyday experience.

Mozart described this beautifully in a letter to his father: the music was already there—he only had to write it down. It reminds me of Michelangelo, who said that the statue was already inside the marble, and he merely had to reveal it. In such moments, the composer is not the actual creator but rather a medium. And I believe the same applies to us performers. In the best moments, we are simply a conduit for the music.

That is reflected in your choice of repertoire…

Exactly. I see fantasy as a force that guides composers in their creative process. It is about much more than just the musical form of a fantasy. Look at the progression: We have Mozart’s Fantasia, which flows like an improvisation, then Beethoven’s “Sonata quasi una fantasia”, Chopin’s Fantasia, and finally Schumann’s “Faschingsschwank”, which unfolds like a kaleidoscope of different characters.

You can observe a fascinating evolution—how Mozart begins with those triplets in D minor, and how similar figures reappear at the beginning of Beethoven’s sonata. In Chopin and Schumann, this idea then expands into entirely new dimensions.

You often speak of fantasy as a path to freedom…

Music in the 18th and 19th centuries was shaped by many formal conventions. In my understanding, these works express a deep longing to transcend those boundaries and explore new realms of freedom.

I find your approach to Beethoven’s sonata particularly fascinating. How do you approach such a well-known work?

Beethoven often breaks the rules, but never arbitrarily—it always arises from a deeper expressive necessity. When working on the Moonlight Sonata, I first tried to forget everything I had ever heard or read about it. At the very beginning, I did listen to some historical recordings, such as Claudio Arrau’s, when I first studied the score. But after that, I followed my own path, trying to feel what this piece truly wants to express.

In the first movement, I perhaps take more time than usual to create this special, almost timeless atmosphere. With such a famous work, there is a great risk of falling into preconceived interpretations. But this music demands a special depth right from the start. You cannot gradually ease into it—you have to dive in immediately.

Chopin’s Fantasia seems to exist in a world of its own…

With Chopin, I always experience these strong contrasts, especially in the middle section, which, to me, feels like a prayer. I imagine a person, alone in a church, in deep connection with something higher. Not necessarily in a religious sense—it’s that universal feeling of hope and depth that every human being understands.

The harmonies in that section are both simple and extraordinary. And then there are those virtuosic passages, which are never just about virtuosity, but always carry a deeper meaning.

Schumann’s Faschingsschwank seems to require a completely different approach once again…

Yes, here we are dealing with a highly vivid, almost theatrical fantasy! It’s like a kaleidoscope of different characters. The first, longer piece throws us right into the carnival, followed by a very intimate second movement. I find the Scherzino particularly interesting – it is both joyful and furious at the same time. The fourth movement is simply magnificent, full of passion and melody, before everything culminates in a rousing finale.

But do you know what fascinates me the most? The psychological depth beneath this colorful surface. When engaging with Schumann, one wonders: Are these really different characters, or perhaps facets of a single personality? The characters are clearly defined, yet there is this astonishing complexity – as if Schumann had discovered this entire wealth of characters within himself.

You also founded your own festival in Verona. What was your vision for it?

The Herbst Musicaux Festival is now seven years old, and from the very beginning, it was more than just a concert series. My goal was to create a true connection between music, people, and nature. That’s why most of the concerts take place in gardens or historic palaces. Each year, we develop a philosophical theme that connects music and people. It is important to me to show that classical music is not just for specialists. True music is medicine for the soul of every human being.

That’s why we also combine it with other art forms—painting, literature, theater. This creates new ways of access because everyone brings their own background and experiences with them.

You also studied sociology alongside music. How does that influence your work as a musician?

That actually benefits me a lot. I enjoy observing, trying to understand what happens on different levels, how things are interconnected. A sociological background provides certain tools for this, but much of it is also about intuition and keen observation.

This perspective helps me understand classical music—how the audience perceives it, how we can build bridges at the festival. It allows me to grasp things on a level that goes beyond the music itself. Of course, I am primarily a pianist, but this broader perspective is very important to me. I feel a deep curiosity and a desire to understand things on a deeper level.

An important part of your artistic development was your time in Moscow…

Yes, studying with Natalia Trull was a formative experience. The Russian piano school has an incredible tradition. It was very intense—demanding a lot of discipline and hard work at the highest level. I learned a great deal, especially about the physical aspects of playing—how to use my body, my hands. That was a completely new dimension for me.

And of course, studying in a different country changes you as a person. You have to open yourself up, question your own beliefs. As an artist, you absorb all these experiences and somehow give them back through music.

You also have a special connection to East Asian culture…

That comes from my family, which has strong ties to the East. Even as a child, I was fascinated by Chinese painting, calligraphy, and small art objects. I could spend hours looking at the characters and wood carvings—I was surrounded by them. These different concepts of beauty—or perhaps they are just different aspects of the same beauty—shaped me from an early age.

How important is chamber music to you alongside solo performance?

For me, these are not opposites—they enrich each other. In chamber music, you learn so much from other instruments, from their unique possibilities that differ from the piano. And when you play with truly great partners, a communication beyond words emerges. You feel what the other means, and in doing so, you discover new aspects of your own playing.

It’s about true, genuine collaboration—not just staying in the same tempo, but communicating on a deeper level. This also applies to a piano concerto: in essence, it is a large-scale piece of chamber music. Even when playing solo, I often think orchestrally, because the piano has this immense range—from the very low to the very high.

What are your upcoming projects?

I will be presenting Fantasies in various countries—starting on January 19 in Arco, near my hometown, followed by performances in Austria, Italy, and Spain. I am especially excited about my solo debut in China with this program. In addition, I have several performances of Grieg’s Piano Concerto coming up.

Apart from that, the plan is simple: keep practicing and give my very best at every concert.